Rady Children’s Hospital reports double win, saving babies and cash

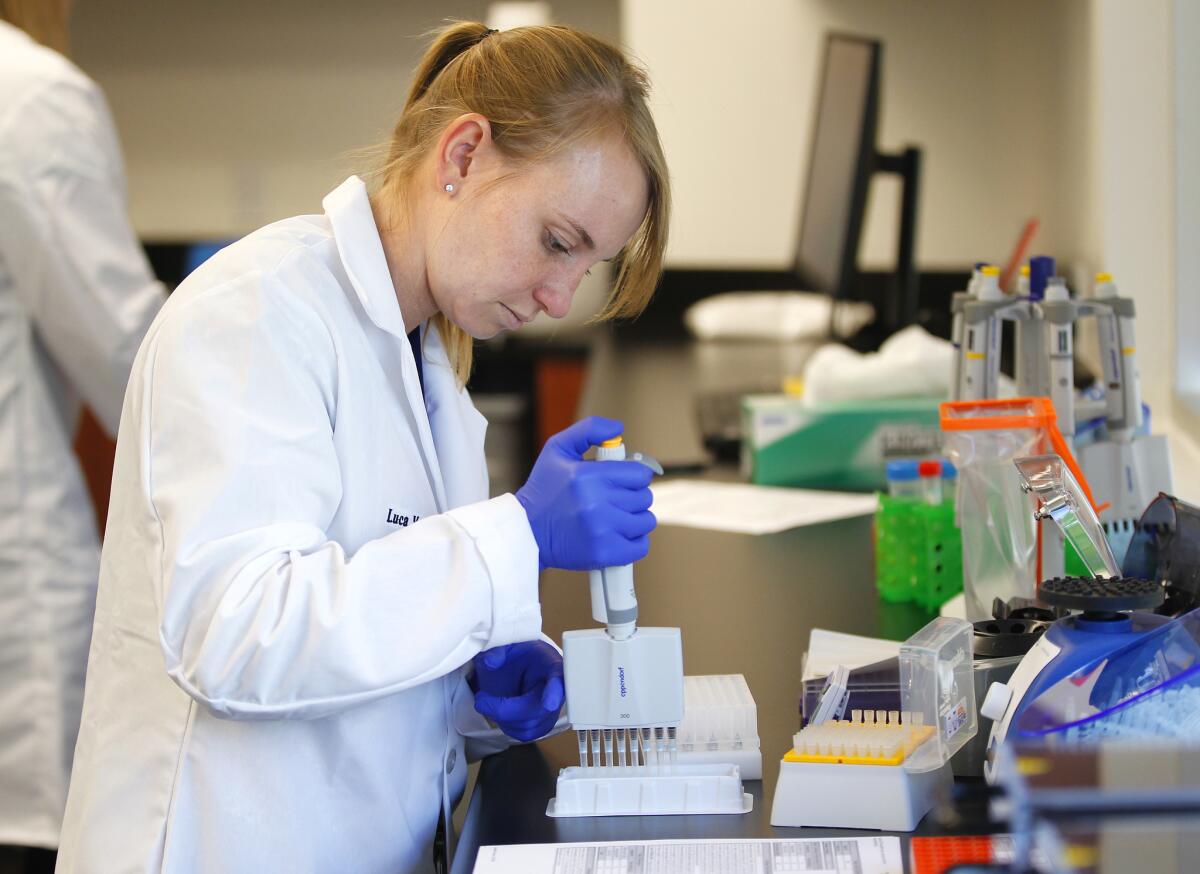

Genomic sequencing was used for infants with unexplained symptoms at five California hospitals

A pilot project aimed at extending rapid DNA-based diagnosis to infants with severe, but unexplained symptoms found answers for 76 different families across five California hospitals, according to a new report to be released by Rady Children’s Hospital today.

What’s more, the write-up shows that a quicker turnaround time of three days, rather than the one to two weeks that is currently common for whole-genome sequencing and analysis, can reduce costs. Analysts found that reducing the length of expensive hospital stays, and the number of unnecessary tests and procedures, net Medi-Cal costs that were hundreds of thousands less than they otherwise would have been if finding a diagnosis took longer.

Conducted by the Rady Children’s Institute for Genomic Medicine in San Diego, the pilot project, which was funded with a $2 million state grant, aims to change the way young patients are cared for throughout California. Dr. Stephen Kingsmore, the institute’s president and chief executive, said that the results returned by the pilot indicate that the approach is viable statewide.

A relatively small percentage of the 20,000 patients admitted to neonatal intensive care units across the state would likely benefit from rapid whole-genome sequencing and diagnosis. That likely means, Kingsmore said, that a few thousand would qualify for gene-based gene-based workups per year for those with unexplained, but deadly conditions such as seizures, respiratory failure and low muscle tone in the first year of life.

“We’re not saying ‘let’s sequence everybody’ we’re saying, very conservatively, let’s accomplish for the state what the report says works,” Kingsmore said. “We are confident that the capacity is already there and we are ready to change the standard of care.”

With the state facing a massive budget shortfall due to the continuing COVID-19 crisis, adding services, even for a particularly-vulnerable and also narrowly-defined segment of the population, won’t be an easy sell.

But being able to show savings might help changes get made.

Researchers calculated that the earlier diagnosis resulted in 513 fewer days spent in hospital beds, 11 fewer major surgeries and 16 fewer invasive tests such as “open” muscle and liver biopsies conducted under anesthesia.

Taken together, those reductions generated about $2.5 million less Medi-Cal spending than would have been the case had patients waited seven days to two weeks for a genetic diagnosis. Accounting for the $1.7 million in total costs generated by rapid sequencing services, the net savings was estimated at nearly $800,000.

Time, it turns out, really is money when you’re talking about diagnosing sick kids.

Outside San Diego, the Rady institute worked with children’s hospitals in Orange County, Sacramento, Oakland and Madera near Fresno, helping each to select patients covered by Medi-Cal, the state’s safety net health coverage for disadvantaged residents.

A total of 178 babies were admitted into the program with 76 having their unexplained symptoms diagnosed through genetic analysis; 55 of those had diagnoses that ended up changing the treatment they were prescribed.

Many of the conditions that genetic analysis was able to diagnose are extremely rare with one in a million incidence rates and eclectic names such as Curtis Laxa 3, DiGeorge Syndrome, Aicardi-Goutieres Syndrome 1, and Timothy Syndrome, a cardiac condition that causes abnormal heart rhythms which, if left untreated, can eventually be fatal.

For the young patient with Timothy Syndrome, Kingsmore said, diagnosis meant immediate readmission to the hospital and treatment that might otherwise have not been performed until it was too late.

“This is why we go the route of decoding the entire genome for these patients, because it’s only by this route that we can catch these extremely-rare conditions,” Kingsmore said.

Making rapid whole-genome sequencing available in neonatal intensive care units across the state, the executive added, will require not just significant training but also an additional Medi-Cal billing code which, so far, has not yet been added in California though one has been approved in the federal Medicaid program.

One thing that the team learned by working with four other hospitals across the state, he added, is that it takes about six months to get local hospitalists up to speed on which cases are most likely to benefit from rapid genetic diagnosis. It is not enough to simply deliver results to patients. An entire system of care needs to be in place, Kingsmore said, if a diagnosis is to properly influence the care that a baby subsequently receives.

“You’ve got to find the baby at the day of admission, and you’ve got to follow them up all the way through discharge home,” Kingsmore said. “What’s needed is not just a matter of sequencing, but an integrated service. If all you’re doing is just attaching a label to the baby, you’ve done nothing.”

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.